#PUBLIC ARCHITECTURE PROJECTS

LOADED SPACE

The Kunsthaus Dahlem opened last year in Berlin as a new public gallery dedicated to postwar modernism, focusing particularly on sculpture – and creating a mini-cultural hub in the west of the city with its neighbour the Brücke Museum. Occupying an existing building, the renovation by Petra und Paul Kahlfeldt Architekten had not only to make fit-for-purpose its fabric but also to work with its somewhat loaded past. Rob Wilson visited and finds a space facing up to its ghosts.

The industrially-scaled building converted by Petra und Paul Kahlfeldt Architekten into Dahlem’s new Kunsthaus – a gallery focussed on postwar modernism – looks at first sight like some redundant municipal boilerhouse or pumping station, sitting incongruously in this well-to-do residential neighbourhood of Berlin bordering the Grunewald forest.

The exterior presents an imposing stripped-classical slab of sand-coloured brick, heavily-corniced but relatively blank on its southern streetside façade, bar a huge central doorway, but to the north punctured by a row of massive vertical windows. Its formal symmetry is in stark contrast to the low-slung free-wheeling concrete form of its immediate cultural neighbour, the Brücke Museum, built in 1967, which nestles more comfortably against the forest, more spreading modernist bungalow than gallery.

And the contrast is a telling one, for these two buildings – and the art they were designed to contain – are almost textbook counterpoints in the troubled course of early twentieth century German cultural, and indeed political, history. For, rather than being an ex-industrial shell, the new Kunsthaus’ home is the former studio of the sculptor Arno Breker (1900-91), one of Hitler’s favourite artists, constructed for him as a “State Atelier” by the Nazi Regime as a sign of favour between 1938 and 1942. Breker’s talent for classically figurative sculpture was quickly harnessed by the Nazi Regime for propaganda purposes, particularly under the patronage of architect Albert Speer, the General Building Inspector for “Germania”, the new capital into which Berlin was being transformed.

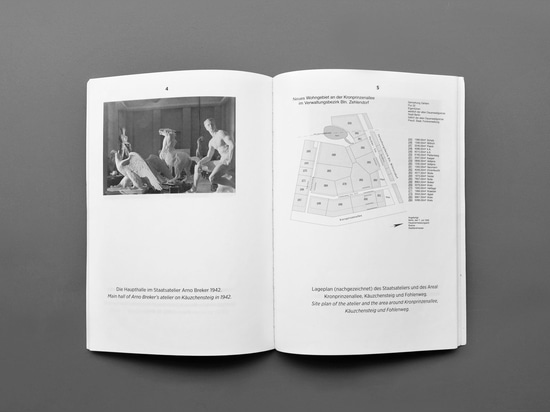

Akin to the fate of the famous actor in Klaus Mann’s novel Mephisto, Breker’s accommodation with the Nazi Regime proved a bit of a Faustian pact, perverting his undoubted talent, yet in the short term giving him enormous opportunities – and the status and wealth that flowed from them: from the gift of a country estate on his fortieth birthday to this enormous atelier. Despite his only fitful use of it due to bombing raids, the surviving photos and propaganda film of the atelier from the time evidence his productivity in this respect, showing it full of promethean, if slightly effete, statues of men, eagles and rearing stallions. All are variously buffed, taught and muscled, gesturing or rearing – and intended for the façades and pediments of the vast new ministries and war memorials planned to be ranged up and down the north-south axis of the rebuilt capital.

Designed by Hans Freese (1889-1953), the building was the first in a planned “art zone” in the city for state-approved artists. As originally planned, this was to have been just one of two studio blocks for Breker, wings to a new villa designed for him too. While simple in detail, the door and window surrounds are finished in fine ashlar stone, while two long blank rectangles of projecting brick either side of the central southern door were intended to receive Breker friezes, no doubt to announce to visiting dignitaries, the workings of a new Praxiteles within.

The south façade, showing the blanks panels either side of the central door, designed to take friezes of Breker’s work.

The plan was simple, consisting of an enfilade of three studios: a large central one with two smaller ones – originally termed “private” and “stone” studios – to either side, all equally lofty at eight metres height and flooded with daylight from the enormous north-facing windows. All the studios were state-of-the-art for the time, with a double-layered glass ceiling concealing lighting for nightworking, built-in floodlights for propaganda filming and photography, a freight elevator, pivoting floors and cranes and embedded floor-rails for moving the huge pieces around, making the studios more like the backstage of a theatre (which it effectively was – the theatre being the Nazi state).

The building survived the war unscathed and for a long time was divided up into artist studios. But in 2013 under a joint initiative, the City, which owns the building, and Senate of Berlin agreed monies to renovate it as a new public gallery space, to be run by the Bernard Heiliger Foundation, named for a prominent post-war West German sculpter who for many years had actually occupied the eastern part of the building as his studio space.

Petra und Paul Kahlfeldt Architekten were commissioned for the job and have done a low-key but thorough restoration of the building, keeping the three main spaces pretty much intact, but with a lot of the key work inevitably invisible: it being the stripping back and making good of the original fabric to create museum-quality spaces.

The one key move has been the extension of the original balcony from the eastern gallery, through a new high-level doorway, to extend the full length of the southern wall of the main gallery space. This has had the effect of bringing down the horizon line of the whole gallery – meaning that the more human-scale works of sculpture now on show are not lost against the overwhelming space – while also providing a more intimate first floor gallery for smaller drawn and 2D work, resulting in a richer spatial circuit to the whole, rather than just a simple linear one.

But most significantly, the new balcony cuts across the old central entrance door, which is now treated as a glazed void with a smaller door set in it, while the main entrance has been moved around the corner to the west side. This cleverly undercuts the mis-en-scène powertrip of the architecture, with its original symmetrical sequence of approach into the main space, designed to shock and awe through its scale. It also practically allows for an entrance space to be sited in the western pavilion, in which ticketing, retail, coats – and no doubt catering for private views – can be accommodated.

The eastern gallery, showing the scale of the windows and doors in the lofty eight metre high spaces.

You thus now approach the sequence galleries from the side, entering first what was originally the “stone” or stein studio, which has been left rawer than the rest, and is the most historically resonant space, with its original chains and pulleys, narrow crane gantry and ladders, all underlining its uncomfortable verticality. It is here that information is displayed about the history of the building, while the subsequent two ex-studio spaces are left free to operate more neutrally as gallery spaces.

The only duff note is the slightly mannered feel to some of the choices and details in the gallery design. The predominant paint colour for the walls, for example, has been cranked up to be an odd institutional grey-ish tone, set off strangely against woodwork in a greeny-grey – a combination that has the hands of a colour-consultant all over it. More problematic is the cod-classical detailing to the columns supporting the balcony and the awkward angled-turn and strangled flourish to the bottom of the stair, which rests on an ashlar footing – as though trying to reference the stripped-classical of the original architecture but getting it a bit wrong, more deco-pomo than successful echo.

But apart from small niggles, this is a successful repurposing of a building that carries more than a few ghosts, into a fine new public gallery space. Its renovation is a careful and successful balance between acknowledging and not eliding the theatrics of the original architecture and its representational loading, but ultimately reworking and moving on from the complexities of its history.