#PUBLIC ARCHITECTURE PROJECTS

PYRAMID SCHEMES

POLITICS AT A COLD WAR RELIC IN BRATISLAVA

Conceived during the brief 1960s liberalisation in Czechoslovakia, before the Soviet crackdown, Bratislava’s national radio station had a public roof garden which connected it out into the city. Abandoned after the fall of communism, it was brought back to life last year as the country’s first community rooftop garden. However, its success, with 50,000 visitors coming for events including concerts, workshops and guided tours, has led to another, if rather more localised, crack-down: this time the eviction of the community so that the radio management can run the space themselves. Chris Luth delivers a blow-by-blow account of a project whose organisers end up being the losers in the politics of space and participation still swirling around this relic of the Cold War.

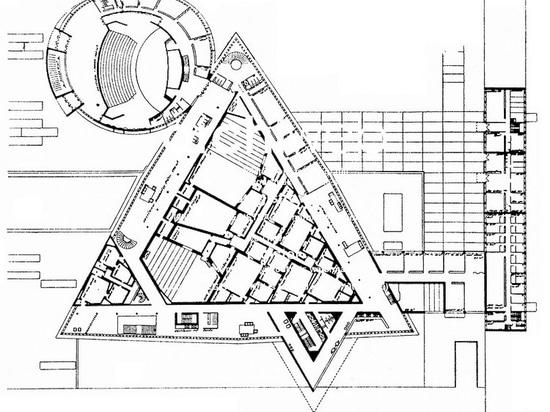

Bratislava, 1963. The competition for a national radio building has no winner. Most entries consist of a low-rise base topped by a tower, but the third prize is slightly more adventurous with a triangular tower and base, the latter flanked by a lentil-shaped concert hall. Architects Štefan Svetko, Štefan Ďurkovič and Barnabáš Kissling are asked to develop the design into a more expressive building: they will end up working on the design for the next six years – and the project for over twenty.

Meanwhile, after years of stifling communism in Czechoslovakia, Slovak politician Alexander Dubček begins to push for greater freedom of expression too. In April 1968, he announces political reforms to create “socialism with a human face”, liberalising the country to encourage greater public participation in politics, the media and culture, as well as decentralising it – creating a federation of Czech and Slovak Socialist Republics, making Bratislava a new capital. The latter is the only new measure that survives after Soviet tanks roll into the country four months later to crush this so-called “Prague Spring”.

The RTVS national radio station tower against the cityscape of Bratislava. (Image courtesy Institute of Construction and Architecture of the Slovak Academy of Sciences)

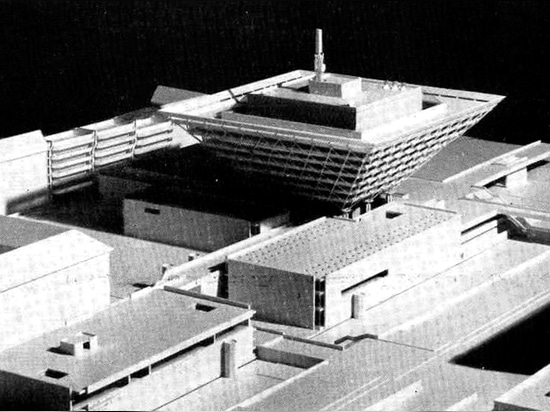

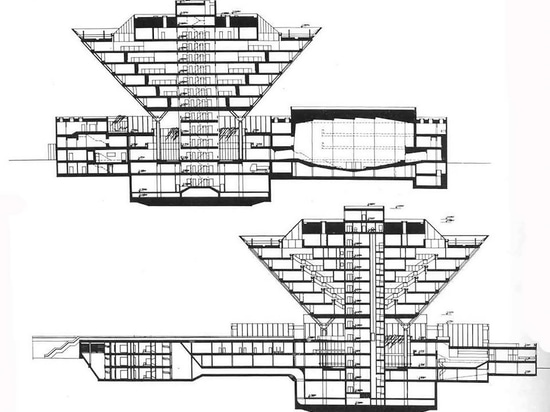

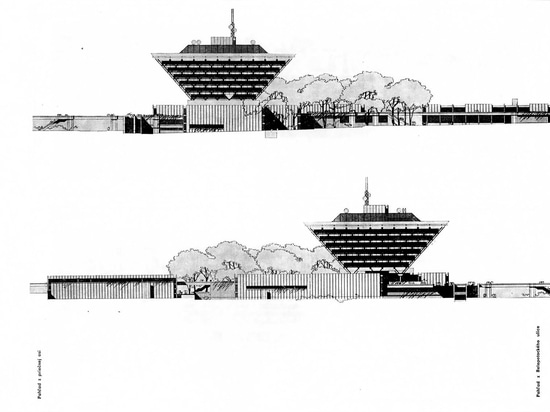

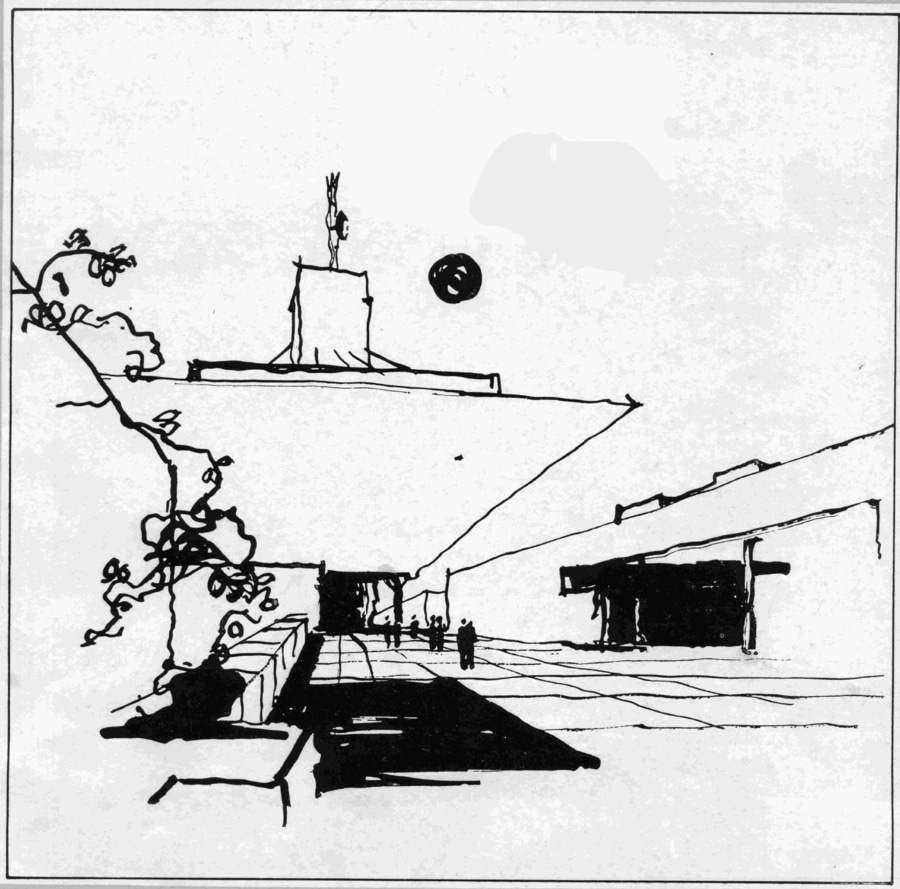

The architects in the meantime carry on working, presenting their final design in 1969, which exhibits two design breakthroughs: firstly the high-rise is transformed into an inverted pyramid – containing the editorial and broadcasting departments – a structural form for which no permanent precedent had yet been built. The other design development is the concept of roof terraces that now cover a rectangular rather than triangular base, containing the recording studios and concert hall, and which extend out into the surrounding neighbourhood via elevated walkways, even bridging the surrounding streets to adjacent blocks – suggestive perhaps of a public broadcaster anchored in the community.

Construction starts the same year, but its ambitious design proves a challenge for the sluggish East Bloc construction industry and it’s only finished in 1984. By that time, Slovak society has become much like the one warned against by George Orwell in his famous novel set in the same year. Paradoxically, having been envisioned as a revolutionary design, once constructed, the inverted pyramid can equally be seen as a symbol of an oppressive state – a brutally overbearing precursor to the slickly meandering CCTV tower of OMA in Beijing.

The radio building survives unscathed through the peaceful Velvet Revolution of 1989 and the ensuing 1993 dissolution of Czechoslovakia into the fully independent Czech and Slovak states. But the transition from centrally planned to market economy leaves its mark on the structure. At some point in the 90s the access to the public roof terraces is closed off and abandoned, left to become covered in weeds, graffiti, broken glass, needles and syringes. By 2012, the UK’s The Daily Telegraph lists the building as one of the ugliest in the world

The RTVS Tower under construction. (Image courtesy Slovenský rozhlas)

Then in summer 2013, during a public workshop called Pioneers of Vacant Urban Spaces, a team of volunteering professionals decides to create the country’s first public roof garden. Calling themselves NA STRECHE, Slovak for “On the Roof”, by the following spring, helped by 16,000 EUR in grants, they prepare to construct it on top of the largest building in central Bratislava, a Tesco supermarket. But just days before construction starts, Tesco cancels the agreement under pressure from a developer eager to keep the community at bay.

But then the volunteers discover the radio building’s forgotten terraces. In July they send a proposalto Radio and Television Slovakia (RTVS), which immediately accepts. So the POD PYRAMÍDOU (Under the Pyramid) project is born and volunteers are called for over Facebook to help scrub the roof.

On September 16, 2014, the roof terrace is opened by two RTVS directors and two POD PYRAMÍDOU members, with the intention – as laid out in the contract they have signed together – to: “support healthy living, diets, education and awareness raising activities, for the protection and creation of natural environments, integration of minorities, youth and for the protection of the health of citizens.” The mayor of Bratislava and the Old Town’s governor join the event, praising their pioneering partnership.

POD PYRAMÍDOU garden... (Photo: Jedlé mesto)

POD PYRAMÍDOU initiators architect Dominika Belanská, human ecologist Boglárka Ivanegová and non-profit sector consultant Martin Kuštek reschedule their jobs to be in the garden almost non-stop, organising grill parties, community workshops and debates, while gastronomic partner MOJE opens a pop-up café. They design and make tables for a socially inclusive Christmas market, buy Christmas trees and employ homeless people as cleaners – all from their own pockets. RTVS provides the infrastructure with its alternative music station booking concerts. Vendors made handsome profits and 18,000 people visit the market: it’s an overwhelming success.

In 2015, the gardening community grows to 60 registered members, with more than 100 active participants. MOJE hosts DJs next to its bar, while RTVS supplements the many community events and public film screenings with live broadcasts and increasingly large-scale concerts, their media exposure helping to attract thousands of new visitors to the roof. After nine months of being open, the roof is transformed into a beloved public space, welcoming an estimated 50,000 visitors – even tourists, the project fostering a real sense of ownership and belonging for the many involved.

But as its popularity increases, the RTVS progressively takes control over POD PYRAMÍDOU. Its director Vincent Štofaník repeatedly warns that the rooftop should be aimed at the “Public”, not the “Community”. Soon after, he demands that the MOJE bar site be taken out of the contract, and that the (decades old) graffiti around the community garden needs to be cleaned off by the volunteers. Then on August 25th RTVS annuls the contract.

All welcome at POD PYRAMÍDOU. (Photo: Fernando Fernandez)

The gardening community has to remove its 81 large planters, fruit trees and garden equipment by November 30th, making way for a new expanded Christmas market with market stalls at much higher rents.

During their very last meeting, on October 21st, RTVS proposes to buy the POD PYRAMÍDOU Facebook community page from the volunteers who’d set it up the year before. By November 7, interviewed by independent newspaper Denník N, Štofaník claims it was actually his idea to open up the terraces under the pyramid and it was RTVS who’d approached the volunteers to participate, not vice versa. Later the volunteers learn that RTVS had actually filed to trademark the POD PYRAMÍDOU name back in May.

Half a century on, the site of the inverted pyramid is still a place of politics it seems, be it on the small stage of its roof terraces, the site of a battle between bottom-up participation versus top-down hierachies. But then as Churchill famously claimed “we shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us”.