#LANDSCAPING AND URBAN PLANNING PROJECTS

Field of Dreams: greening the urban landscape

Integrated green spaces in towns and cities around the globe are as manifold as the forms they take.

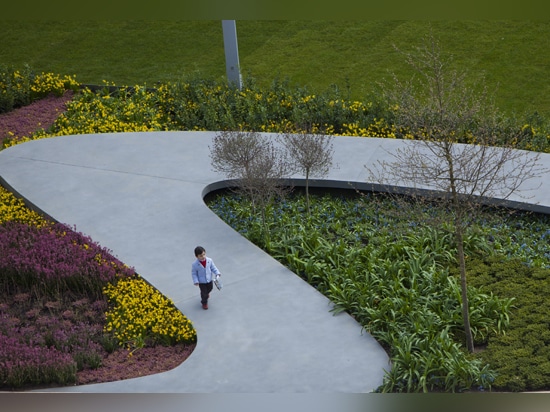

Landscape architecture in cities is a hugely fertile – and expanding – field. Audacious, vast schemes for urban parks, gardens and green roofs are mushrooming all over the world. This is partly due to a new, growing movement, which flouts the age-old hierarchy of gardens being subsidiary to buildings. Landscape urbanism, as it’s called, privileges horizontal landscaping over vertical architecture.

What’s more, many urbanites appreciate bold, contemporary gardens, while these in turn are widely recognised as offering psychological benefits – they counter the stress caused by congested streets and our exploding urban populations.

More importantly, an increasing awareness of climate change and an urgent sense of ecological responsibility felt by designers and the public alike have led to sustainability being the bedrock of many projects. This has seen the widespread rise of practices such as cleansing and reusing stormwater (rainwater that runs off imporous, pollutant-coated surfaces such as concrete) and boosting biodiversity.

Designers are also keen for their projects to mesh with the fabric of the city rather than be separate, alien entities; the word ‘linking’ constantly recurs when green spaces are described as bleeding into the surrounding streets. By the same token, designers also value context, often creating schemes that reference the history of a project’s location. And landscape architecture plays a key role in the regeneration of formerly industrial, derelict areas, making it more closely allied than ever to urban planning.

Perhaps the most iconic example of landscape urbanism is New York’s The High Line (originally a railway line raised off the ground and now a park). But more ambitious still, perhaps, is Singapore’s coastal Gardens by the Bay development, which occupies 54 hectares of reclaimed land. Designed by Grant Associates, this is a public, sustainability-led project par excellence. It has leaf-shaped gardens with inlets of water between each one allowing breezes to penetrate and cool the park. Aquatic plants absorb chemicals in the water, reducing pollution. And ‘food gardens’ cultivate plants used as ingredients in the park’s cafés and restaurants.

This £350m (€410m) project also features two shell-like, climate-controlled conservatories, designed by architects Wilkinson Eyre, which contain the climates and plant life of the two habitats which will be most affected by climate change – the Mediterranean and (high-altitude, equatorial) Cloud Forest regions. Both boast a computer-controlled shading system. Near them are ‘Supertrees’ – 50m-high structures that provide shade and incorporate solar panels that generate electricity, as does a biomass boiler which powers the conservatories’ cooling system.

A concern for sustainability also underpins the 500-square-metre Burnley Living Roofs at the University of Melbourne. Co-designed by the practice Hassell and the university’s green-roof technology and urban horticulture researchers, these comprise a Demonstration Roof, which showcases 14 green-roof types and various methods of irrigation, the Research Roof dedicated to quantifying the benefits of green roofs and the Biodiversity Roof which encourages colonisation of indigenous plants, hollow logs and a stream by insects, birds and reptiles. The project aims to determine the best plant species and forms of soil for city roofs and to demonstrate that green roofs can reuse stormwater, reduce buildings’ energy use, cool the urban environment and bolster biodiversity.

Green roofs are not only a burgeoning trend but many are now conceived on a mammoth scale. Chicago-based landscape architects Hoerr Schaudt have revitalised Nathan Phillips Square, which faces Toronto City Hall, the city’s municipal government. This incorporates the city’s largest publicly accessible green roof – formerly a windswept podium which had been closed for a decade – a pool, sculpture court and reflecting pool (converted into an ice rink in winter). Its tousled-looking planting was chosen to withstand Toronto’s harsh climate – purple, pink and yellow sedum and, in areas of deeper soil, feathery grasses and indigenous perennials. At different heights, these provide texture as well as changes in colour as the seasons progress.

By contrast, Eastside City Park in Birmingham – co-designed by London-based architects Patel Taylor and French landscape architect Allain Provost – is less overtly pastoral. Part of the regeneration of the city’s Eastside quarter, which was heavily bombed in the war and filled with derelict Victorian factories, this 3.4-hectare park incorporates a canal and 21 fountains. Patel Taylor say they approached the brief primarily as urban planning and secondly as landscape architecture. Laid out in a formal grid, and punctuated by monumental Corten steel columns that nod to the site’s industrial history – and even look rather melancholy – the project is also sustainable since it has transformed a brownfield site, has good public transport links as well as cycle routes and pedestrian paths to the city centre. Eastside City Park might appear to be austerely geometric, yet it’s softened by colourful planting – salmon-pink poppies, orange daylilies, red-hot pokers and irises.

Parallels can be drawn between Eastside City Park and Parco Dora in Turin, the work of German practice Latz + Partner. Both occupy what were formerly industrial areas. But the latter – once home to a Fiat steelworks and Michelin tyre factory flanking the river Dora – pays homage to an even more extensive industrial heritage. A grid of steel columns – a skeletal vestige of the steelworks, and all that remains of them – and cooling towers dominate parts of the park. Original canals and slurry tanks have been retained, albeit under the banner of sustainability: rainwater is now harvested for irrigation. The park can be surveyed from a walkway suspended from rust-red steel columns, though softening this industrial aesthetic are trees and meadows aplenty.

Meanwhile, at Danish fabric company Kvadrat’s HQ at Ebeltoft, conceptual art collides with bucolic scenery in a park co-created by artist Olafur Eliasson and architect Günther Vogt. Called Your Glacial Expectations, it’s open to the public. Eliasson is known for his installations featuring mercurial elements, from fog to water, and here he has placed five elliptical mirrors flat on the ground. Inspired by glacial pools, they reflect the ever-changing sky. A mowed pathway steers visitors between the mirrors and groves of trees that include Norway maple, oak and Japanese Pagoda trees. Moveable chairs, which can be turned to face different views, also grace the site, making the garden more interactive.

In short, a modern-day vision of Arcadia is becoming a more common sight in our cities. Pastoral charm aside, this greening of urban spaces is driven by pragmatism: a need to address climate change and offer respite from urban overcrowding.