#PUBLIC ARCHITECTURE PROJECTS

Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture by Olson Kundig

Unlike the typical museum model, in which exhibition and back-of-house spaces are separated, the recently opened 105,000-square-foot Olson Kundig-designed Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture—located on a prominent corner of the University of Washington’s Seattle campus—showcases gargantuan fossils in bare, daylight-infused galleries.

Throughout the warehouse-style building’s three levels, these striking display rooms mingle with fully-glazed research laboratories, workrooms, and interactive learning alcoves, giving visitors visual access to the preservation process, and encouraging a more accessible educational environment.

According to the museum’s director, Julie Stein, transparency was central to the project’s vision. Previously, the Burke had been located next door in a 1962 structure with only two galleries—compared to the new building’s six—and the bulk of the institution’s 16 million biological, geological, and cultural objects were hidden from view. “At the old museum, I’d take visitors down to the basement to see the students and researchers working with the collections,” says Stein, “People had no idea all of that was down there—it was like a secret world.”

More critically, the former building was grievously inadequate. It lacked proper temperature controls, so objects were placed in metal cases with gaskets to protect them from rapid changes in humidity, taking up already limited space. In the early 1990s, the Burke, which is fiscally administered by the university and funded in part by the state, had already run out of room—it wasn’t until 2009 that it was able to pull together the resources to put out a request for proposals. Tom Kundig was selected because he “truly understood what we were trying to attempt,” Stein says, “which was a building that invited people into nature. He talked about growing up in Spokane with a true love of the outdoors, of rock climbing, of the forest, and it really resonated.”

Although Kundig is a staunch advocate for adaptive reuse, the board was adamant about constructing a larger building for the $100 million project. Kundig’s approach for the new glass-and-steel structure, which has 66 percent more space than its 66,000-square-foot predecessor, was to make it as simple as possible — “a big rational box,” as he puts it, that would be easily adaptable for future growth. “It was not a stylistic endeavor, but a scientific one,” he says.

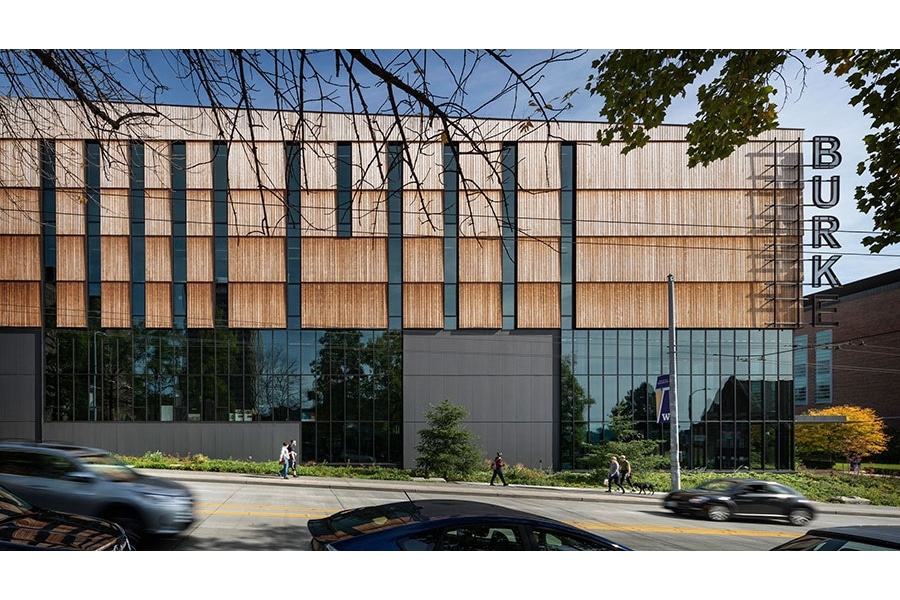

Inside the building—which, located on a sloped site, features a lower lobby in addition to its three floors—the architecture is minimal, allowing for the objects and activities to be at the foreground. The façade is fully glazed at the lobby levels, connecting the museum to the streetscape, while the upper levels are clad with swaths of sustainably engineered southern pine. A shed roof inspired by traditional Coast Salish dwellings nods to the institution’s Northwest identity.

The specific placement of the museum departments amongst the galleries was determined by the wants and needs of each division; since paleontology and archaeology had been in the basement for 50 years, they jumped at the opportunity to be near the skylights on the third level, according to Stein. The culture division, which comprises delicate artifacts that can be easily damaged by light, such as silkscreen prints, ceramics, photographs, and textiles, is located on the first level, away from exterior walls, leaving biology on the second. The decision to have researchers on view was very thoughtfully considered. In the old Burke, glazed laboratory prototypes were constructed to test out how workers felt about being exposed to the public. The staff eventually acquiesced to the condition, the only caveat was that the museum would have to hire more researchers to work on the weekends: “If the lights are off, we are not fulfilling our promise to the public,” explains Stein.

On the site of the now-demolished old structure, a garden and programmable outdoor learning areas help to announce the museum’s presence. Whereas the former Burke was hidden within its urban block, Kundig’s design announces the instituion’s offerings with what Stein calls the “jewel box”—the fully glazed southwest corner that beckons passersby with massive whale and mastodon skeletons. “It sends the signal that this is a building full of magnificent objects that are awe-inspiring—and that you’ve got to come in and take a look.”